“So Let Us Persevere . . .”

“If we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.” —commencement address at American University, Washington, June 10, 1963

“And death shall have no dominion” —Dylan Thomas

*

Rarely has a November passed by that this blog has not paused to pay respects to the memory of President John F. Kennedy. We keep an “eternal flame” of our own lighted not only because of a feeling of personal connection to him—from an Irish Catholic family kinship, and having been taken as a toddler to a 1960 campaign stop at an airport in the South, and being just old enough to watch the post-assassination and funeral coverage on a black-and-white TV—though these would be reasons enough. We repeatedly bring President Kennedy to our readers, or vice versa, because of what he stood for, what he accomplished, and what he symbolizes.

What Does ‘John F. Kennedy’ Mean?

It may be that, despite the limitations of what he was able to accomplish during his too-brief presidency, because of the ideals he represents, because of the hope and activism he still inspires, President Kennedy is more influential postmortem than during his lifetime. And it’s possible that the murky, still nebulous circumstances of his death (by whom, really, and why?) add to the mystique of the Dead King, the Slain Prince, and all that might have been possible, and might still be possible, if we summon his spirit. He dwells now on the mythological level, in the realm of ideas and legend. (This may explain the success of Jacqueline Kennedy’s posthumous establishing of a “Camelot” myth. At least in the public mind, there was no Camelot connection with the Kennedy White House before Nov. 22, 1963: Mrs. Kennedy’s myth-making began with an interview with Theodore H. White, author of The Making of the President 1960, a week after the assassination.)

Now, on the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination in Dallas (November 22, 1963, was also a Friday), many other, more learned voices are commenting on the accomplishments and significance of President Kennedy’s “Thousand Days” in office—what he did and what he failed to do. We only wish to honor his long-standing commitment to peace; his refusal to be cowed or bullied by the military chiefs or the CIA during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 (especially after he was burned by the CIA’s brilliant idea for an invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in 1961); his reluctance to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam and his intention to withdraw troops; his establishment of the Peace Corps, etc.

Now, on the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination in Dallas (November 22, 1963, was also a Friday), many other, more learned voices are commenting on the accomplishments and significance of President Kennedy’s “Thousand Days” in office—what he did and what he failed to do. We only wish to honor his long-standing commitment to peace; his refusal to be cowed or bullied by the military chiefs or the CIA during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 (especially after he was burned by the CIA’s brilliant idea for an invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in 1961); his reluctance to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam and his intention to withdraw troops; his establishment of the Peace Corps, etc.

He supported, though cautiously at first, civil rights and desegregation of public facilities, especially in the South. He had a plan for expansion of medical coverage for the poor and elderly that became what we know as Medicaid and Medicare, and he supported strengthening voting rights. Much of his desired or proposed legislation was left to his able successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, to push through Congress—thus the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 through expansion of Social Security.

Because of the historical circumstances of his time, the national priorities, and his own proclivities, Kennedy was more focused on foreign affairs than on domestic policy (the Soviet Union’s building of a wall through Berlin, supporting Fidel Castro in Cuba, and beginning to build ballistic missile silos in Cuba, etc.). But he also called the nation to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade (this too had national security components), and his vision was realized by the successful mission of Apollo 11 in 1969.

About the Assassination, and the “Conspiracy” Controversy

And, of course, on this fiftieth anniversary, many media pundits and establishment historians are busy pouring concrete over the hardened conventional wisdom about the lone gunman, the “case closed,” the truths proved by the Warren Commission Report, etc. This is not the occasion—and perhaps not the place—to expound our views on the assassination, but we have read enough books and articles, seen enough documentaries, and attended enough panel discussions to be thoroughly convinced that the president was shot at by multiple shooters, and we doubt that Lee Harvey Oswald was one of them. (As for the plausibility of a “conspiracy theory,” remember that the attacks of 9/11, too, resulted from a conspiracy.) The most convincing explanation we have found of why Kennedy was killed is in the sober and methodical JFK and the Unspeakable by James W. Douglass, excerpted below.

About the presidency of John F. Kennedy, among many other excellent sources, we recommend:

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House (1965), by the former special assistant to the president

Theodore C. Sorenson, Kennedy (1965), by the former special counsel to the president

Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917–1963

Robert Dallek and Terry Golway, Let Every Nation Know: John F. Kennedy in His Own Words (2006), book and CD. “Perhaps the best of all the books on JFK.” —Senator Edward M. Kennedy

For more about the assassination:

James W. Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters (2008)

Jim Garrison, On the Trail of the Assassins: My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy (1988), by the former district attorney of New Orleans who brought the only case relating to the assassination to trial (1967)

Robert J. Groden, The Killing of a President: The Complete Photographic Record of the JFK Assassination, the Conspiracy, and the Cover-Up (1993). Groden served as a photographic consultant for the House Select Committee on Assassinations.

Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment (1966, 1992)

Films:

Thirteen Days (2000, on the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962), directed by Roger Donaldson

JFK, directed by Oliver Stone (1991)

The Men Who Killed Kennedy (1988), a comprehensive, multi-part British production, refreshingly independent of biases of mainstream U.S. media

Other sources about John F. Kennedy:

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Warren Commission Report (digitized)

And more here . . .

JFK and the Unspeakable

JFK and the Unspeakable

“John Kennedy’s story is our story, although a titanic effort has been made to keep it from us. That story, like the struggle it embodies, is as current today as it was in 1963. The theology of redemptive violence still reigns. The Cold War has been followed by its twin, the War on Terror. We are engaged in another apocalyptic struggle against an enemy seen as absolute evil. Terrorism has replaced Communism as the enemy. We are told we can be safe only through the threat of escalating violence. Once again, anything goes in a fight against evil: preemptive attacks, torture, undermining governments, assassinations, whatever it takes to gain the end of victory over an enemy portrayed as irredeemably evil. Yet the redemptive means John Kennedy turned to, in a similar struggle, was dialogue with the enemy. When the enemy is seen as human, everything changes.”

—James W. Douglass, from the Preface to JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters

*

For a generous sampling of President Kennedy’s speeches, we recommend the book + CD Let Every Nation Know: John F. Kennedy in His Own Words by Robert Dallek and Terry Golway (2006). Each of 34 speeches is introduced, but transcripts are not provided. For transcripts, see the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum, under the tab “JFK.”

*

Related Topics at Levees Not War:

Marching on Washington for Economic and Social Justice

In Honor of Medgar Evers and Res Publica

Tom Hayden, SDS and SNCC Alums: Happy 50th, Port Huron Statement!

How the World Has—and Has Not—Changed in 50 Years

*

[ This post also appears at DailyKos ]

*

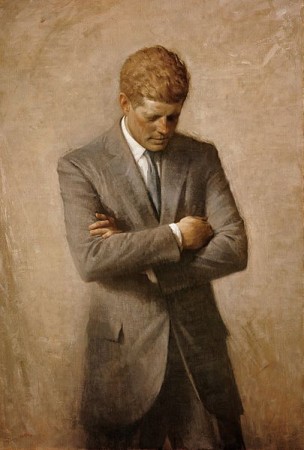

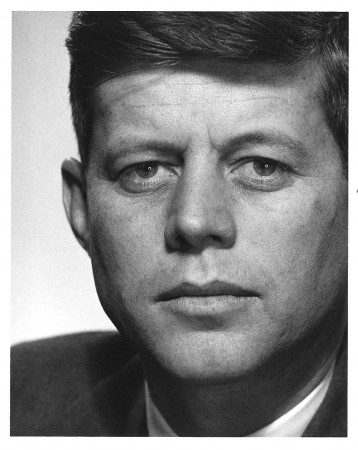

Photograph of John F. Kennedy, 1952, by Philippe Halsman; official White House portrait of John F. Kennedy by Aaron Shikler (1970). Photograph on book cover by Jacques Lowe, Coos Bay, Oregon, 1959.

*